Lone Jack

In the half-century since I last saw you, I’ve never once thought about writing your story. It’s not that I didn’t care. It’s that I didn’t really know you.

But recently, documents came into my hands – ones mom had saved for years. Finally, some of my questions were answered. Some remained.

Let me tell you what I know and perhaps the ghost of you can fill in the missing pieces.

You were born on the family farm in 1918, just a few months before the end of the Great War. You were the Golden Boy; the sun rose in your smile, or at least that’s what your sisters thought.

The farm was a stone’s throw from a cemetery on land donated by your great-grandfather. You knew every name there, even the ones erased by wind and weather. I wondered, years later, if the hardest one for you to bear was the one for your mother or the one for your son.

Fort Laramie, Wyoming

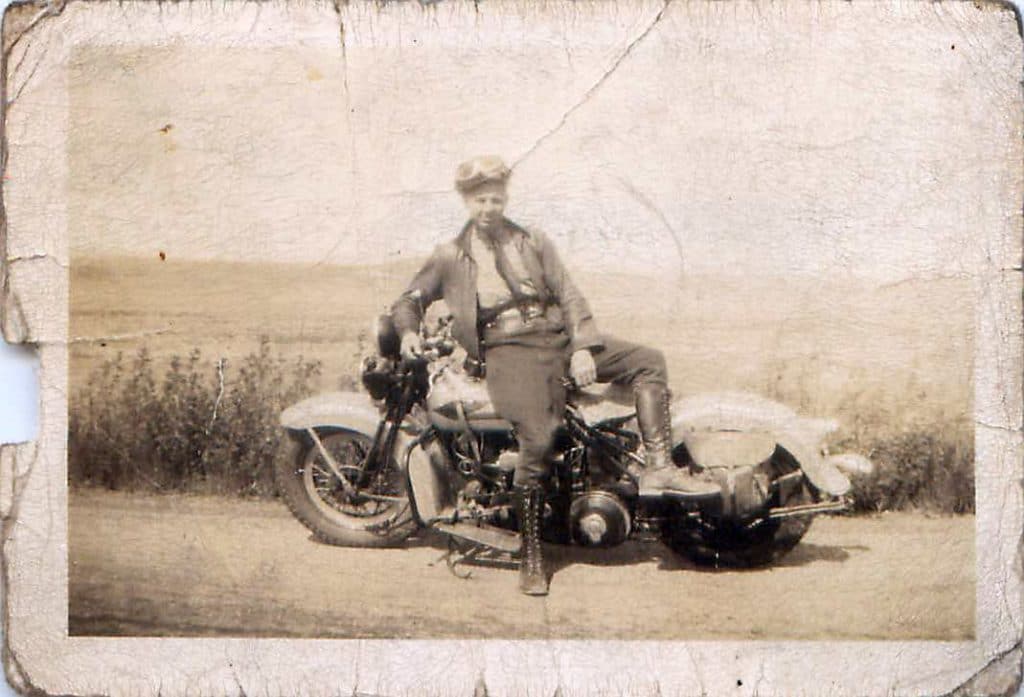

Over the years, your family moved a few times, but not before giving you the chance to be the adventurer I think was at your core.

In your teens you jumped on a motorcycle and roared off to Wyoming. Did you know that decades later I visited those same places?

I read a letter you wrote home, saying that one day you hoped the Great Plains would be your home.

It never was.

St. Joseph

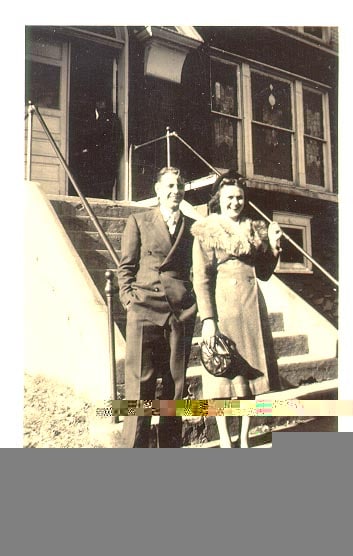

By 1940, you were ready to settle down.

Married on Easter Sunday, you stood waiting at the end of the aisle in the church your father helped run. Your wedding was the event of that spring; the minister later said he feared the balcony, overpacked with all of your friends, would collapse under the weight.

Your bride wore a hand-sewn satin gown and carried Easter Lilies. Your mother wore purple, your father dressed, as he always did, like a dandy.

In July of the following year your son was born; two years later your daughter.

Fort Hood

Pearl Harbor happened and for awhile, marriage and children saved you from the war. But in 1944, the draft caught up with you. Mom and your parents drove you to an induction center at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. Then, you and hundreds like you were shipped to Texas.

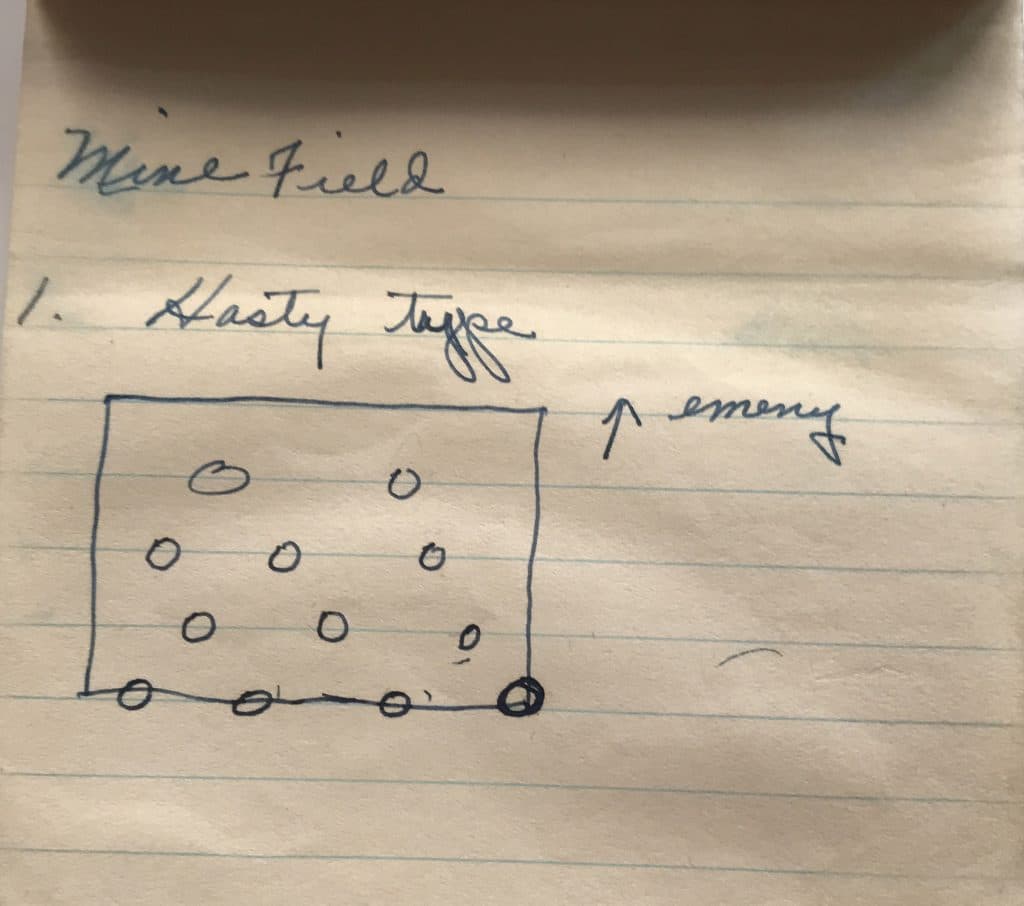

I don’t know how long your training took place before you left for the carnage in France. But it was there, at Fort Hood, that you filled your notebook with diagrams of observation posts, foxholes, and the correct way to lay a mine field.

You were 26, and learning how to kill. I’m not sure that ever squared with you.

France

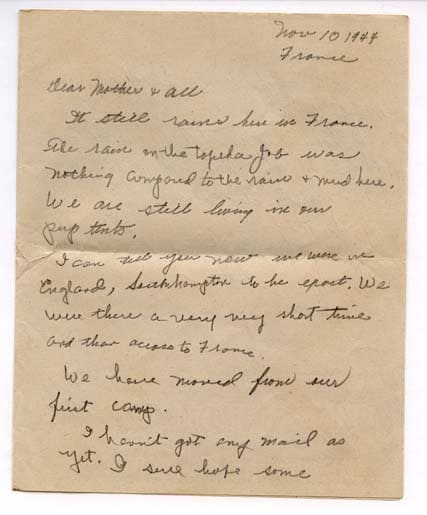

Finally, in the fall of 1944, you arrived in France, probably somewhere around Normandy. In a letter dated November 10, you said the rain “on the Topeka job” couldn’t compare to the “rain and mud here”.

While your division was pushing the Germans out of Eastern France, did you know that one brother-in-law lay dead 40 miles north of you, while another slogged island-to-island in the Pacific?

Dieuze

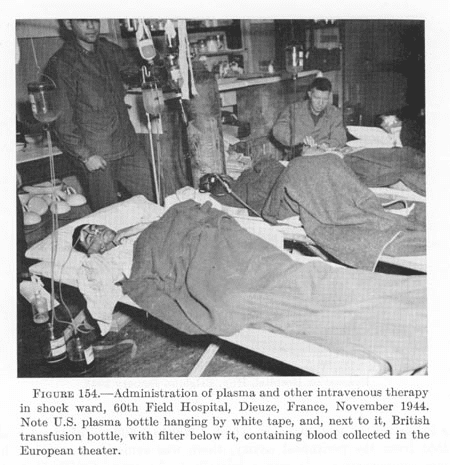

On November 26, after only a few weeks at the front, your body was half-pulverized by a mortar round. After lying in the mud for 12 hours you were found and taken to a field hospital.

Even now I can imagine rivulets of rain running through your hair and down the back of your jacket, so cold and wet your blood never dried.

Although saved, home was still far away.

Springfield

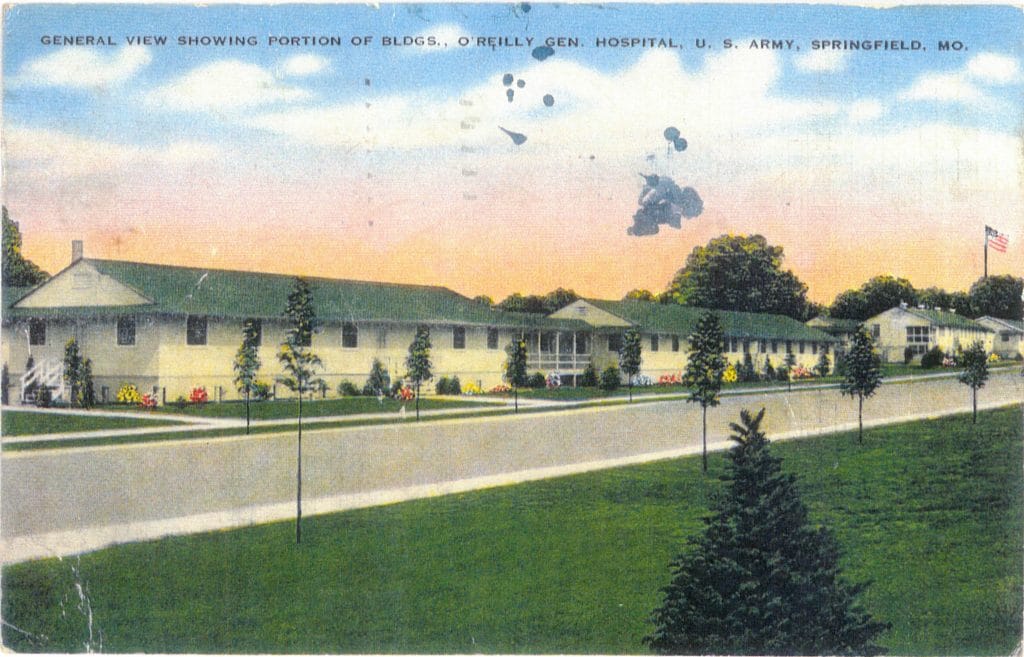

From November 28, 1944, until June of 1945 you were shuttled from hospital to hospital.

First the field, then Paris, Oxford, England, Bristol, the Queen Mary, New York City, and finally Springfield, Missouri.

St. Joseph

I always thought you were released around Easter of 1945, when this photo was taken of you, your mother and sisters. But in going through old papers I found a postcard dated June 27, 1945; you were still in Springfield, waiting for another operation.

But later that year, you did make it home. Back to the white two-story house that once belonged to your parents. I still remember the Weeping Willow at one end of the yard and the Russian Olive at the other.

Life, at least from my young point of view, seemed settled.

San Diego

But in 1957, you moved us to California.

In that strange city, so far from the ease of the Midwest, we lived in an upscale neighborhood in a Spanish-style stucco with an unobstructed view of the bay and the ocean beyond.

I wish I knew if you came to regret the move. My sister said your stress was high and the work difficult. Did PTSD lurk somewhere in your back pocket making it that much harder?

I’ll never know.

Santa Ysabel

When I was barely 15, we all piled into the Ford and drove out to see desert wildflowers.

On the way home, you stopped breathing.

While mom drove frantically, trying to find a fire station, I climbed in the back seat where you had pulled yourself and tried my best to breathe my life back into yours.

But I could tell from your unfocused gaze and the blue of your lips that you were already gone.

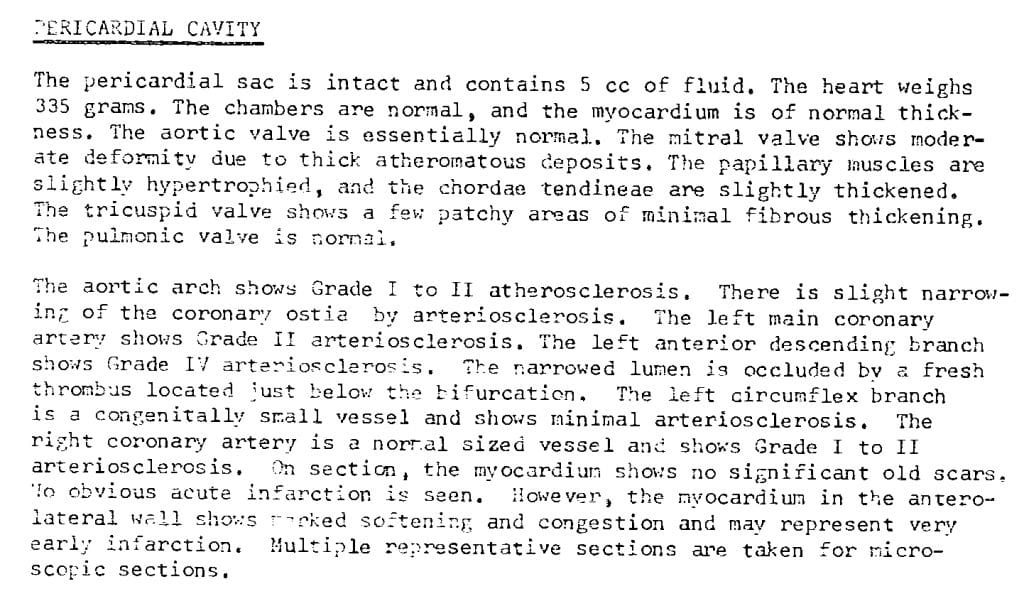

San Diego County Medical Examiner’s Office

Years later I showed your autopsy to my own doctor. He said nothing could have saved you; this, he added, was not the first time your heart had given out, it was just the most catastrophic.

Did the first attack come via the German flak that ripped you apart? Did you die on that November day in 1944, not realizing it until twenty years later?

Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery

People ask me – what was your dad like, was he funny, did he like to play games, did he share your curiosity?

And always, my answer remains the same.

I didn’t really know him.